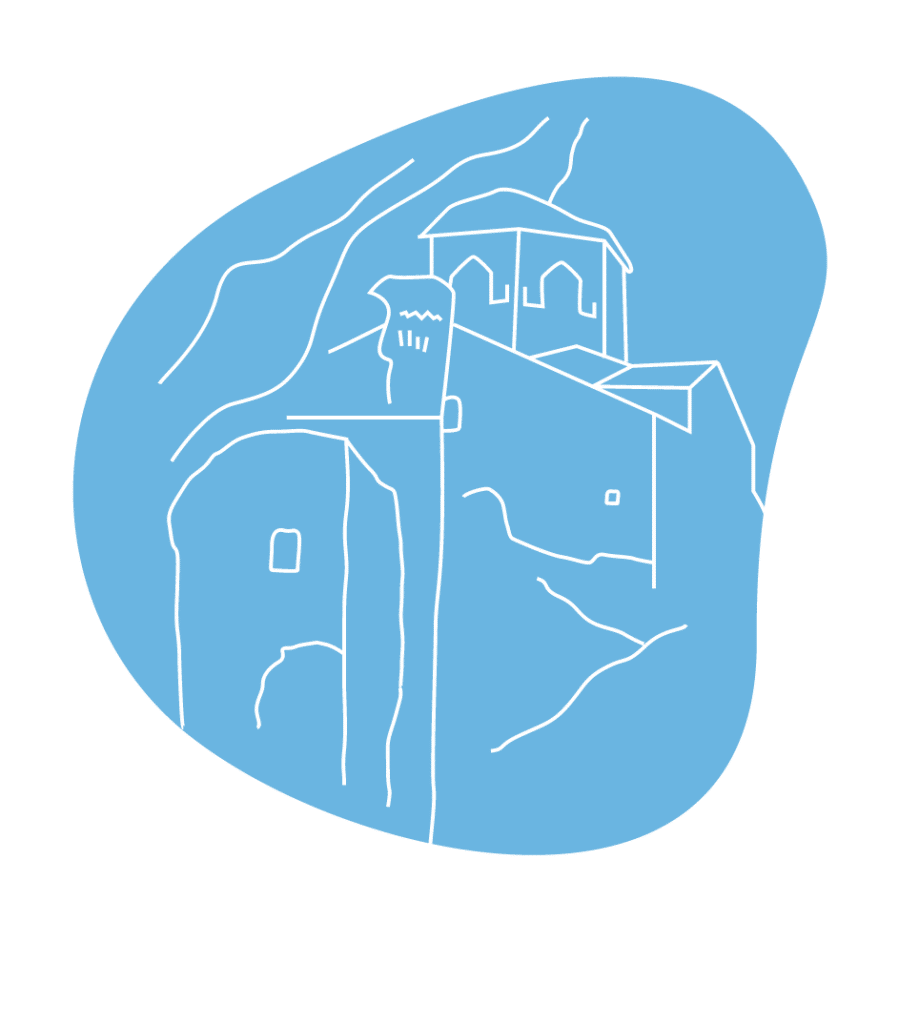

Built at the foot of Klinitsa, the Aimialon Monastery looks like an architectural wonder in nature, having played at the same time a pivotal role in the history of the martyrdom of Theodoros Kolokotronis’ brother and his companions, who, amidst persecution by the Ottoman authorities, found refuge in a linos right next to the Monastery.

A linos is a traditional agricultural building that served as wine press for the grapes and the rough boiling of the must. A group of six Greek klephts led by the brother of Theodoros Kolokotronis, Giannis, took refuge in such a building in 1806, and met a martyr’s death by a Turkish detachment alerted by a monk of the Aimialon Monastery.

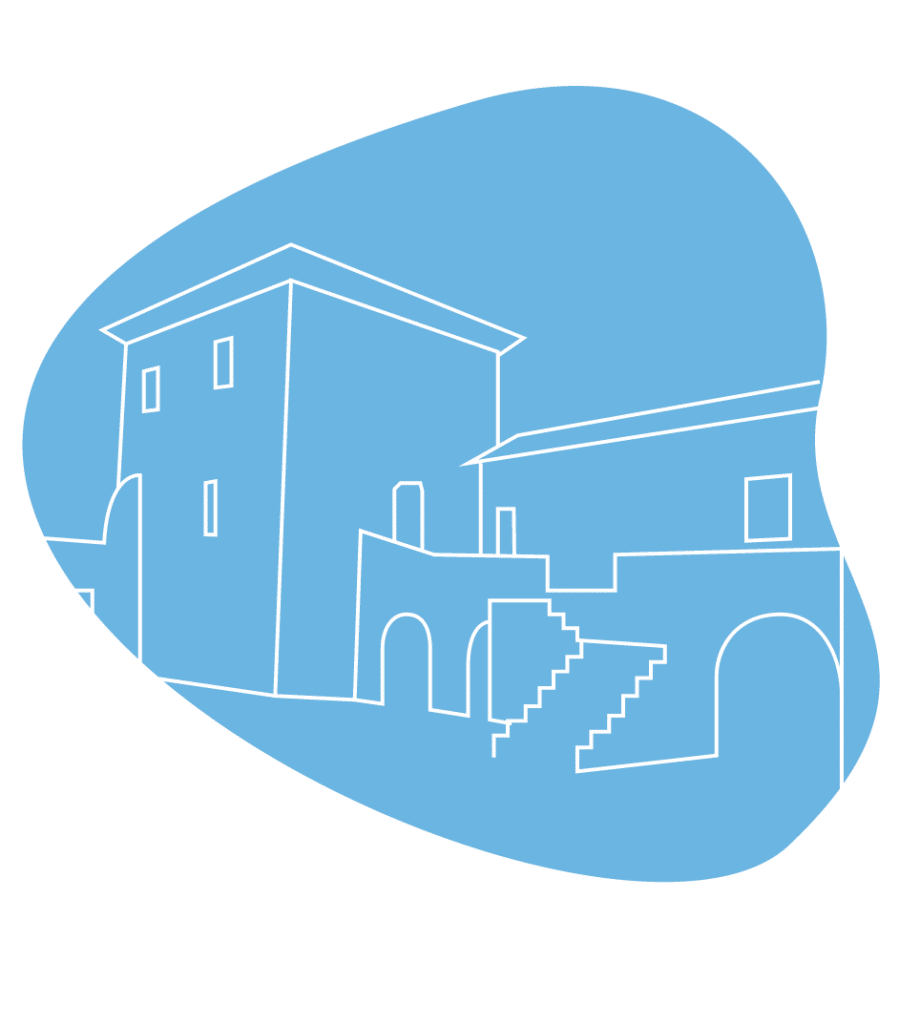

At about 70 km from Tripoli and 2.5 km from Dimitsana, at an altitude of 885 m at the foot of Klinitsa (a hill of Mount Mainalo), “wedged” on the southern side of a steep rock, dominates the impressive Holy Monastery of Panagia Aimialon. The Monastery was refounded shortly before 1600 AD by the hieromonk Grigorios Kontogiannis and his sister, nun Eupraxia Kontogianni, a fact that is also confirmed by the inscription preserved on the south side of the Monastery’s katholikon. It is said that it owes its name to the origin of its two founders, who came from the village of Aimialoi in Alagonia, Messinia.

Over the centuries, the Monastery has undergone many conversions and additions, and today it is spread over two wings that form a T, with the horizontal top lying almost entirely inside the rock and the vertical line, clearly shorter, containing a three-story tower.

Its katholikon is a single-aisle basilica, a large part of which is under the rock. Its icons were created in the beginning of the 17th century by the brothers Dimitrios and Georgios Moschos, who followed the standards of the Cretan School.

Regarding its contribution to the struggle for the independence of Greece, it was just as important as that of the other monasteries in the region. During the Orlov revolt, a part of it was burned down, while in the Revolution of 1821, it offered valuable financial assistance, as its abbot, Parthenios F. Papadopoulos, was a member of the Filiki Etairia (Society of Friends).

In 1925, and while it was in decline, it was merged with the Holy Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, Stemnitsa, until 2006, when, with the approval of the Holy Synod, it was re-established as an independent men’s monastery and as such it functions until today.

Heading off from Dimitsana, shortly before we reach the Aimialon Monastery, two large cypress trees enclose a small stone building, the Linos of the Kolokotronis family. It is a traditional building that was used to press the grapes and boil the must in the production of wine.

There, according to the historical sources and the narration of Theodoros Kolokotronis himself, on February 1, 1806, a group of klephts, consisting of his beloved brother Giannis (who was called Zorbas because of his character), his cousin George (Captain George from the village Aetos, Triphylia) and four other men, pursued by the Turks, took refuge in Aimialon Monastery for the night, despite the fact that the leader of the Greek Revolution had advised them not to approach it.

Those years were very difficult for Greek klephts. As early as 1805, Ecumenical Patriarch Kallinikos V had issued an excommunication against the klephts of the Peloponnese, and indeed, an encyclical that was read in all churches, obliged priests and citizens to betray them to the Turkish authorities.

In one of the vineyards of the Monastery, the six men found a monk pruning and asked him for food, as well as to convey their needs to the abbot. The monk offered them food, but then, instead of conveying the information to the abbot, he handed them over to the Turks.

A short time later, a Turkish detachment arrived in the area and laid siege to the wine press, in which the six men were locked up. After a long battle, the Turks, using sulfur and wax, managed to set fire to the building that was full of vines, as a result of which the six Greeks attempted a heroic exit. On their way out, they killed many members of the Turkish detachment, but they themselves eventually met a martyr’s death.

According to tradition, Theodoros Kolokotronis watched the death of his brother and the other brave men from the mountain across, Klinitsa, where a large cross has been erected in memory of the event. The Turks did not respect the bodies of the dead klephts. Their heads were first sent to Dimitsana and then to Tripoli, where they were hung on a plane tree in the central square, which today bears the name of Theodoros Kolokotronis.

The Linos of the Kolokotronis family has been completely renovated and is open to the public, while a marble inscription has been placed on one of the walls of the building describing this story, which took place a few years before the Greek Revolution broke out en masse.

Διαδρομες

Ιερά Μονή Ζωοδόχου Πηγής Στεμνίτσας

Το γραφικό και ιστορικό χωριό της Δημητσάνας αποτελεί βασικό θεματοφύλακα ιστορικών και λαογραφικών παραδόσεων του ελληνικού γένους. Στη βιβλιοθήκη της, εκτός από τα εμπλουτισμένα με 35.000 τόμους βιβλίων ράφια.

Αρχοντικό των Δεληγιανναίων

Το οίκημα δεσπόζει στον Πάνω Μαχαλά του ιστορικού χωριού Λαγκάδια, το οποίο, εκτός από σημαντικούς χτίστες, χάρισε στην Ελλάδα την περίφημη οικογένεια των Δεληγιανναίων, προεστών του Μοριά πριν από την Επανάσταση. Από την οικογένεια Δεληγιάννη προήλθαν και δύο Πρωθυπουργοί στα χρόνια μετά την απελευθέρωση.

Dimitsana Historic Public Library

The picturesque and historical village of Dimitsana is a key depository of historical and folklore traditions of the Greek nation. In its library, apart from the shelves enriched with 35,000 volumes of books, the visitor can also admire important relics and memorabilia from various moments of the glorious past.